- Home

- Grant Golliher

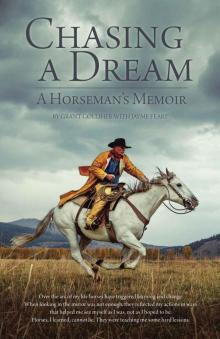

Chasing a Dream: A Horseman's Memoir

Chasing a Dream: A Horseman's Memoir Read online

Author’s Note

This is a work of nonfiction. Nothing has been made up. I have made every attempt to be truthful. However, as this is a product of my memory, I acknowledge that some people may remember things differently. In the interest of privacy I’ve changed some of the names of people. There are no composite characters or manipulations of time. The dialogue comes from my memory. I’ve done my best to render it accurately.

Grant Golliher

Cowriter’s Note

All of the information in this book came from Grant and his wife Jane, who are responsible for the veracity of this work. In some instances they contacted other persons who helped clarify or verify Grant’s memories. My role has been to help Grant find the story among all the events of his interesting life, to help him organize his life story into a narrative, and to edit his writing. I returned each draft to him to verify I had not, with my work, changed facts or context.

Jayme Feary

Copyright © 2017 by Grant Golliher

All rights reserved.

Designed by Betsy Christiansen

Grant Golliher

www.diamondcrossranch.com

PO Box 315, Moran, WY 83013

[email protected]

TO MY WIFE JANE,

WHO MADE THIS BOOK A REALITY.

INTRODUCTION

With a little thought, a person can scan the arc

of his life and identify all the major turning

points: but only afterward with the benefit of

time and distance. For me, certain horses have

triggered learning and change, because when

looking in the mirror was not enough, they

reflected my actions in ways that helped me see

myself as I was, not as I pretended or hoped

to be. Horses, I learned, cannot lie. They were

teaching me some hard lessons.

CONTENTS

I: THE BREAKING POINT

II: THE ROOT OF IT ALL

III: MISTAKES AND MOUNTAINS

IV: NEW BEGINNINGS

V: THE END OF RUNNING

VI: OUR NICHE

EPILOGUE

THE BREAKING POINT

THE BREAKING POINT

1

BELLEVUE, IDAHO, 1984

The gelding, Cisco, hung limp from his lead rope, his head two feet off the ground, his legs splayed. I had tied him to an aspen tree, where he had pawed a hole before falling. The grass under him was pressed flat, the ground rubbed raw. His tongue hung limply. His eyes were milky and dull.

My wife Locke (“Lockee”) sprinted to him and covered her face with her hands. “Oh no, no, no. This can’t be happening. Cisco!”

I stood there staring. My God! I thought, I can’t believe it. This is my fault. Not an hour earlier, I had tied and hobbled Cisco, one of our top polo prospects, in the shade while Locke and I drove into Bellevue to eat a quick lunch with friends. I had been determined to break him of his pawing habit. “I’ll teach you,” I had said. “You want to paw? I’ll hobble your front feet and tie you until you learn some patience.”

If I understood anything in those days, it was how to solve problems with horses. I knew all the techniques and tricks to get results. I knew how to fix my horse’s pawing and the impatience that caused it: make him stand hobbled and tied long enough to learn.

But a whisper, a still, subtle voice in the back of my head had warned me. Maybe I shouldn’t leave him while tied and hobbled, I thought. But I dismissed that voice like I usually did in those days, ignoring my intuition, my actions, and their consequences. Now, when I look back on my life, I realize that across the warm blue sky of that summer, clouds were gathering.

I was succeeding beyond my imagination at my dream career—training and competing on polo horses—and I had married Locke, a talented and beautiful cowgirl musician from a prominent family back east, but at that moment Locke and I stared dumbfounded at a horse we thought would elevate us in the polo world, now hanging dead from a tree like an outlaw.

What a tragic accident, I thought. But I was so naïve. I had no idea that the horror of that moment would pale in comparison to future events. That summer my life was galloping headlong toward a cliff, and I didn’t know it. Now I understand that the fall was inevitable.

With a little thought, a person can scan the arc of his life and identify all the major turning points: but only afterward with the benefit of time and distance. For me, certain horses have triggered learning and change, because when looking in the mirror was not enough, they reflected my actions in ways that helped me see myself as I was, not as I pretended or hoped to be. Horses, I learned, cannot lie. They were teaching me some hard lessons.

Right before Cisco’s incident, I had purchased another promising young polo prospect, a beautiful black Thoroughbred gelding with four white socks and a white blaze. He cost $2,500—a huge sum of money back then. Even after Cisco died, Sly World gave us hope.

SLY WORLD

Sly World gripped the bit in his teeth and bolted frantically across a wet polo field toward an irrigation system, a metal pipe about chest high supported by a series of wheels. I was not a rider but a passenger powerless to stop, slow, or turn him. I could only sit deep and watch the wheel line grow closer. I wondered if he’d jump it, attempt to turn ninety degrees, or barrel through it. He slammed into the system, knocking the entire wheel line several feet across the turf, almost fell.

I jumped off, held the reins, and checked to see if Sly was hurt. “You idiot” I said. “You have a screw loose. I can’t deal with you any longer. That was your last chance. I’m going to get rid of you before you kill somebody.”

Sly World had run away many times before. When I had ridden him inside the corral he would ride around fine, but when he was carrying me out in the open he would pick the oddest times to grab the bit and bolt. Without warning he would go from a walk to a flat-out runaway, galloping blindly with no thought of his safety. It was a terrible feeling to cling to him running out of control, but I was determined to break him of the habit. The only method I knew was to ride the guts out of him until he got over it.

His purchase price had been more than what we normally paid for good prospects, but he was a talented specimen with a striking black coat and perfect conformation. However, his eyes were small for his head—what horse people call “pig-eyed,” a characteristic that old-timers said indicated a horse couldn’t be trusted. No problem, I had thought. I thrived on challenging horses, and often picked the hard ones on purpose because I believed tougher horses made better mounts. Enough hard work, miles, and repetition would break any horse. I had developed a reputation for working with the tough ones, and I believed that in time Sly World with his talent would come around and be a great horse.

One day our black-and-brown cowdog Squirt was following behind Sly World minding her own business. Sly looked back, cocked an ear toward Squirt, and let her have it. His hoof nailed Squirt between the eyes. A thud like a hammer hitting a watermelon. Squirt yelped, collapsed, and started seizing, blood flowing from the gash between her eyes. I dropped Sly’s lead rope, ran to Squirt, and knelt beside her. I applied pressure by holding my handkerchief to her forehead. “Locke, come quick! Squirt’s been kicked.” I yelled as I scooped her up and we jumped into our old truck. Locke drove like a lunatic to the vet.

We both loved that dog, but Locke adored her. Squirt was hers, she had declared many times. In the vet’s office we waited with our chins in our hands. The vet treated Squirt for several days, and then, unable to do more, sent her home. He didn’t know if she would recover.

This dog was too important to us. She had to get b

etter. For two weeks she fell and convulsed. Her uncontrollable bowel movements made our cabin smell like a mixture of dog poop and vomit. Locke fawned over her and pleaded with her to get well, but she did not.

“Locke,” I said, “maybe it’s time we put Squirt to sleep.”

Locke’s eyes narrowed into her familiar squint. Her tone hardened. “You’re not putting my dog down.”

“She can’t go on living this way,” I said. “And the vet bills are piling up. We can’t afford this anymore.”

Locke screamed. “This dog is going to be fine! You’re not putting my dog down.” She glared at me, and her body vibrated with anger. I had seen the transformation many times before, but this was one of the worst. As I often did, I walked out the back door to escape her rage.

“Don’t you walk out on me.” She stormed outside and her eyes settled on a pitchfork leaning against the cabin. She snatched it and pointed its tines at my chest. “I’ll kill you!” she said. “I’ll run you right through. Don’t think for a minute I won’t.” She sprang forward.

I wheeled, sprang back, and scrambled up the hill behind the cabin and sat there among the sagebrush perched on a rock until well after dark. I hoped she wouldn’t start shooting at me with one of our deer rifles. She was an excellent marksman and had threatened me with our guns before. I felt trapped, an enemy to my own wife. Suddenly Sly World’s behavior made sense to me. I felt an overpowering urge to bolt.

As usual, Locke eventually calmed down, apologized, and went on like nothing had happened. I was wrung out. I would rather have been beaten with a club than with her words. A layer of pain covered my heart.

Locke came to accept that Squirt needed to be put out of her misery, but the decision had to be hers. The vet euthanized Squirt, and we buried her in the sagebrush behind the cabin, a rock for a tombstone. Despite my efforts to fix him, Sly World remained a dangerous horse. I could not in good conscience sell him as he was unpredictable and might hurt someone. Locke and I decided we better dump him, so we sold him for $400, the price of dog food.

At Squirt’s graveside we hugged and cried and asked ourselves what was happening to us. What we thought had been our two best prospects, Cisco and Sly World, were gone. Our dog was dead and our marriage was in trouble. In the wake of these tragedies, melancholy ushered in a short period of calm, but it would not last.

Locke would brag to others about how wonderful I was, and then at home she’d rail at me. Familiar phrases like “I hate you!” and “You’re a sorry piece of shit!” flew through the air like darts, and stuck. Our finances were in shambles, and although I didn’t know it at the time, my insides were beginning to churn with the realization that our highway to success had narrowed into a rutted jeep trail. Frustration and disillusionment can force a person to search his soul. Pain and heartache were about to launch a journey that would change everything.

THE ROOT OF IT ALL

THE ROOT OF IT ALL

2

PALISADE, COLORADO, 1957

With a large butcher knife in her right hand Mom slashed her left wrist and forearm again and again. Dad was outside doing chores before leaving for work at the Cameo Power Plant.

I was only six months old, too young to remember. My sister Jan, then three, recalls walking into the living room and seeing Mom talking on the phone to her pastor, blood pulsing from her forearm, soaking her blouse, and reddening the white phone and the armrest of her blue velvet recliner. Mom casually told Jan, “Go back to your bed, honey. It’s okay.” She then told the pastor that Satan had appeared and convinced her to kill herself.

When my dad, Joe Golliher, came inside from doing chores that morning, he said, “Oh, Jeanne. What have you done to yourself?” He took the bloody handset from her, wrapped her arm in a towel to slow the bleeding, and then called Dr. Bliss, our family physician who directed him to hurry her to his office. When Dr. Bliss saw her wrist, he rang St. Mary’s Hospital ten miles away in Grand Junction and then rushed her there himself.

The doctors at St. Mary’s concluded that the knife had severed too many tendons. Mom’s arm would have to be amputated at the elbow. One doctor dissented, claiming he could save her arm.

The slashing had been the culmination of a darkness that had been creeping over my mother, a depression that may have started postpartum and grown from there. She had been filled with anxiety and would go for days without sleep.

Fortunately after extensive surgery, the doctor managed to save her arm, and she began a slow recovery. Her life revolved around healing and rehab. To help her and to ease the pressure of raising four children, Dad farmed my older brother Clay, my sisters Kathy and Jan, and me out to various friends and relatives.

He sent Jan and me to live with his sister, my Aunt Florence and her husband Oscar, who lived in a nice middle-class home in the suburbs of Denver. I became the center of attention, and bonded closely with Aunt Florence, Uncle Oscar, and their youngest daughter Millie, twelve, who doted on me.

Grant as a toddler enjoys a little ride on his first “horse”. Jeanne and Joe Golliher pictured outside their home in Palisade, Colorado with Grant at about age three.

Six months later, Dad retrieved us, and for weeks I padded around in my walker bumping from room to room looking for Aunt Florence and Uncle Oscar.

As a toddler, I would wander unnoticed out of the house and down to the irrigation canal, a swift, thirty-foot-wide river from which the area farmers irrigated their crops. Each year, dozens of children in the West drown in irrigation canals. One time a neighbor found me walking the canal’s edge, our Weimaraner dog Chris staying between me and the canal to block me from falling in. The neighbor took me home, and for years Dad laughed when he told the story.

When I grew into boyhood, I swam in the canal with my older brother and sisters. Dad demanded I wear an old red-and-white-checkered life jacket he pulled from the garage. One day while it sat drying on the bridge above the canal, one of the kids accidently knocked it into the water. It sank like a lead fishing weight. It was so waterlogged it was no wonder I had trouble swimming in it. Dad grinned and said it was amazing how well I could swim without it. The story became another of his favorites.

My friends and I spent hours playing tag under the bridge. Whoever was “it” had to jump off the bridge upstream and float down trying to tag one of us as we clung to the pillars in the rushing water. Or we would dive down to the bottom of the deep canal to see who could bring up the biggest rock. Shivering from the mountain water, we would lie on the bank and cover ourselves with dirt warmed by the sun.

Someone had tied a gunny sack to a rope that hung from a big cottonwood tree on the bank of the canal. We leaned a thirty-foot cherry-picking ladder against the cottonwood and, holding onto the rope with one hand and the ladder with the other, climbed to the top, swung out over the canal, and flipped into the water like seals. Sometimes we would scale fifty feet up the tree, leap, and send the water splattering.

Neighbors often passed by and asked who was supervising us. “Don’t you know that canal is dangerous?” one asked. “Where are your parents?”

Seeking relief from her depression, Mom desperately searched for answers in the form of spiritual guidance. She dragged us along with her, and we became church-goers. Dad would not go except at Easter or Christmas, and whenever Mom would talk about God he would grumble, “Oh Jeanne, you’re just a religious fanatic.” His criticism hurt her deeply, but she was undeterred. Tagalongs on Mom’s spiritual journey, we jumped with her from church to church.

No matter what her difficulties, Mom was always willing to stop and pray for anyone. Her prayers comforted me, especially after one of my frequent nightmares.

3

PALISADE, COLORADO, 1964

Ever since I can remember I have experienced vivid dreams while sleepwalking. Often I would wake up in another part of the house. One night I dreamed I was fighting a deer. I leapt out of bed in my underwear, tore my brother’s prized deer mount off the wal

l, grabbed its antlers, and wrestled it to the ground. I awoke to scratched and bleeding legs and deer antlers broken in two.

Late one night I left my room in the basement, sleepwalked upstairs, sat in the bathtub, and turned on the faucet. The water woke me, and though I felt foolish sitting there in my underwear, I figured, Might as well just take a bath since I’m here. So I did.

Another time I sleepwalked upstairs into our living room where I crawled into a corner behind an old lounge chair. I awoke crying and screaming, Mom shaking me asking, “What’s wrong Grant? What’s wrong?” I didn’t know, but I was so relieved to be back in the real world.

My nightmares made me feel ridiculous and embarrassed, but they continued as I grew older. During a backpacking trip in the mountains with some buddies from school, I dreamed someone was stealing my sleeping bag. Barefoot, I ran up the rocky mountain pursuing the thief. Unable to catch him, I awoke agitated, my feet bruised and bleeding. I hobbled back to camp mumbling, “I hate these dreams. I don’t understand why I do this,” and then crawled back into my sleeping bag. The next day my buddies had a good laugh. On the hike home my sore feet made carrying my backpack agonizing.

Dad often took us kids on camping trips. To keep me from wandering off in my sleep, he would tie a rope to my foot and tie the other end to my older sister Jan. At Lake Powell we were camped on a cliff overlooking the water. The next morning Jan woke up with the rope wrapped around her neck, and Dad had another joke to tell: “What would have happened if Grant had sleepwalked off the cliff? Poor Jan would have got strangled.” It was all very funny to him. He laughed and laughed.

My mother never felt overwhelmed to the point of suicide again, but she continued to slip into dark depressions. No treatment worked, but religion provided some relief.

I was free to roam pretty much at will. Around the age of ten I began spending lots of time either at friends’ homes or camping out in the mountains behind our house with our mules. Skeeter, my mule was my best friend.

Chasing a Dream

Chasing a Dream Chasing a Dream: A Horseman's Memoir

Chasing a Dream: A Horseman's Memoir